By Virginia Davies, CFO, American Fuel Resources

A Strategic Resource the U.S. Has Yet to Fully Acknowledge

In 2001, the OECD Nuclear Energy Agency released a report titled Management of Depleted Uranium that pointed to a reality few were ready to acknowledge: depleted uranium (DU) is not waste. Properly processed, it is a strategic material with civilian, industrial, and national-security applications. At the time, world enrichment capacity exceeded demand, new reactor construction was lethargic, and DU “tails” were viewed almost exclusively as a storage problem.

Twenty-five years later, the United States has accumulated roughly 750,000 metric tons of DUF₆, stored above ground in cylinders across two sites. At current processing rates, the existing backlog of tails will not be eliminated until after 2074, and that projection assumes enrichment does not accelerate. With the Department of Energy (DOE) planning to expand enrichment capacity, the volume of DUF₆ will only grow. The OECD’s question from 2001 now lands squarely in today’s energy and national-security conversation: if this depleted uranium has beneficial uses, why aren’t we reusing it?

A Structural Roadblock: DOE Is the Sole Processor

One answer lies in how depleted uranium (DU) has been handled in the United States. The Department of Energy (DOE) remains the only entity that processes DUF₆, and it does so at sub-commercial prices. That structure prevents the emergence of a private-sector recycling industry. No commercial operator can justify investing in new facilities, technology modernization, or downstream applications when the only existing competitor is a government program charging artificially low rates.

As a result, the United States has never developed a DU processing ecosystem that includes converting DUF₆ into DUF₄ for defense metals or extracting fluorine-bearing chemical components for advanced industries. DOE’s processing system is designed solely to stabilize DU for disposal, not recycle it for reuse. This is the central misalignment: the U.S. government built an approach optimized for storage, not for extracting the valuable components of this depleted uranium.

A Backlog Growing Faster Than We Can Process It

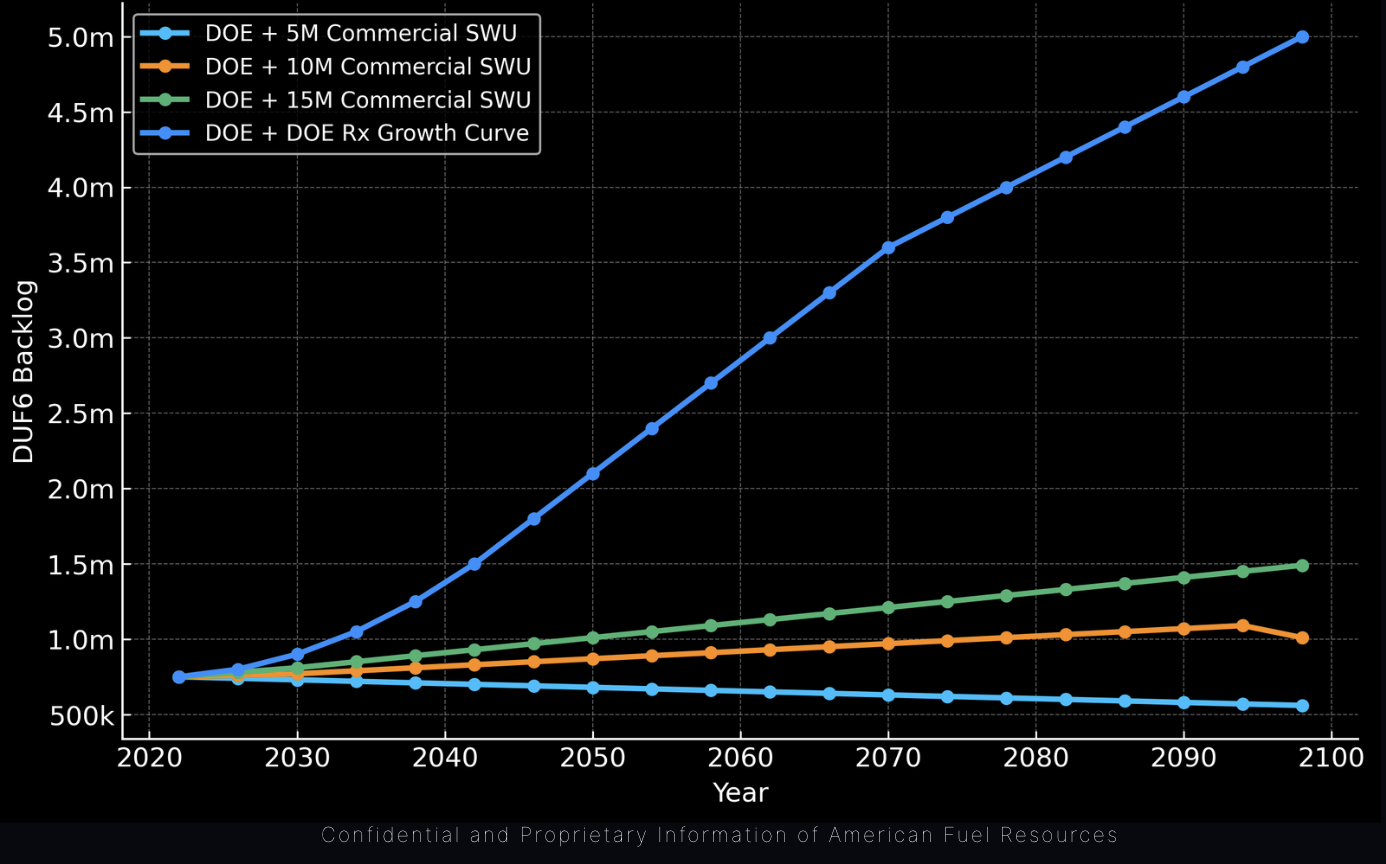

The American Fuel Resources/Green Salt graph illustrates just how severe the imbalance is. The U.S. is currently storing nearly three-quarters of a million metric tons of DUF₆, while DOE’s two operating plants process only about 15,000 MT per year. At this pace, the existing material alone would take half a century to stabilize.

Meanwhile, new DU tails are arriving faster than before as commercial enrichers scale up to meet HALEU demand, support new reactor projects, and help satisfy the accelerating electricity needs of large data centers. The graph included below shows just how dramatic the projected growth in DU stockpiles will be across different enrichment scenarios.

This is not just a logistical challenge. It is a massive opportunity. The United States is stockpiling a material that, if commercially processed, could provide critical inputs for defense programs, semiconductor manufacturing, radiological shielding, and nuclear fuel conversion. It is an extraordinary opportunity to realize the value of this depleted uranium.

National-Security Consequences

For decades, enrichment in the United States was dominated by foreign-controlled or foreign-state-owned enterprises. When the companies enriching uranium are not American, the incentive to build U.S. downstream industries disappears. That dynamic contributed to the erosion of domestic capability in areas that rely on DU-derived products.

These downstream sectors are now becoming strategically important. High-density metals obtained from depleted uranium support defense applications. Radiological shielding is a fast-growing market. And the United States imports 98 percent of the AHF required for nuclear fuel conversion and semiconductor etching, an import dependency that has clear national-security implications.

In an era of supply-chain insecurity, DU reuse is not simply a niche industrial option. It is a matter of national security.

The OECD Identified the Opportunities Early

The OECD’s 2001 report outlined several civilian and commercial applications for DU, including shielding materials, catalysts, counterweights, and potential roles in certain reactor fuel cycles. Those projections have only strengthened.

Today, the radiological shielding market is expected to reach $2.3–$3.3 billion by the mid-2030s. Specialty fluorine gases obtained from DU such as SiF₄ and BF₃ derived from fluorine components contained in DUF₆ are now a combined $1 billion annual market. Depleted uranium metal is a substitute for tungsten, a critical mineral the U.S. imports heavily and which has been repeatedly flagged for supply-chain risk.

The market signals are clear: DU remains a highly valuable industrial feedstock that the U.S. has simply not processed at scale to take advantage of these opportunities.

What Modern DU Recycling Looks Like

Modern deconversion technology for DU, unlike DOE’s legacy systems, is built around reuse. One processing line can convert 9,000 MT of DUF₆ per year into two high-value outputs: DUF₄, which is required for defense-grade uranium metals, and AHF, which is essential for conversion facilities and the semiconductor industry. The system of deconversion draws on proven DOE/General Atomics intellectual property under exclusive commercial license.

Instead of preparing DU for burial, this modern approach transforms it into valuable materials that feed directly into critical supply chains.

A Convergence of Need and Opportunity

For the first time in decades, U.S. policy, industrial demand, and geopolitical pressures are aligned to support the growth of the U.S. commercial industry. Enrichment is expanding, semiconductor manufacturing is a national priority and nuclear power is being reinvigorated as a cornerstone of clean-energy development needed to meet demand. As a result, the United States is actively rebuilding domestic supply chains for critical minerals and strategic materials development needed to support the growth of the semiconductor industry and the dramatic increase in electricity demand.

Recycling DU is not an isolated industrial endeavor. It is a foundational element of restoring a resilient, closed-loop nuclear fuel cycle in the United States.

Conclusion: It Is Time to Start

For more than two decades, the United States has treated depleted uranium as a problem to be managed rather than a resource to be harnessed. The OECD warned early that this perspective ignored substantial value. Today, with a massive stockpile, accelerating enrichment activity, and rising demand for DU-derived materials, that value is clearer than ever.

The data makes the case unmistakable: the backlog is enormous, DOE’s current processing capacity is insufficient, and the industrial applications are significant. America has spent 25 years storing a strategic resource it has never attempted to use.

It is time to stop viewing depleted uranium as waste. It is time to treat it as the strategic material it has always been and begin extracting the value contained in this resource from the nation’s own nuclear fuel cycle.